First Steamship 7th December 1825 Landed In Calcutta "Enterprise"

Origins of Waghorn's Idea for Reducing the Transit Time for Mails to India

Two events influenced Waghorn's ideas about speedier communications between India and England. The first occurred during his participation in the First Burmese War. He was impressed by the accomplishments of a small steamship - the Diana. This 32 horsepower, 89 ton river and coastal passenger steamer was the first of its kind in Indian waters. Launched in 1823 at Kidderpore, she was bought by the Bengal Government for use on the Arakan coast for towing men-of-war into place for attacks and for the transport of passengers up the Irrawaddy. The ever practical Waghorn, noted the tremendous advantage derived by the expedition from the steamer.

The second event occurred when he met Captain James Johnston of the steamer Enterprize at the conclusion of the first steam voyage from England to Calcutta via the Cape. Waghorn was the pilot who brought the Enterprise up the Hooghly to Calcutta on her arrival in India.

...

|

Paddle Steamer Enterprize

[National Maritime Museum, London] |

Captain Johnston had journeyed from Calcutta to England by sailing ship up the Red Sea and then overland through Egypt. He was an advocate of steam navigation and personally favoured the Red Sea route to that by way of the Cape of Good Hope.

In 1825, the Calcutta Steam Committee offered a prize of 20,000 rupees to the first steam vessel that could make the 17,700 kilomtre trip from England to Calcutta and back twice at an average rate of 70 days or less. Captain Johnston journeyed to 67.7 meters long, displaced 479 ton, was equipped with two 60 horsepower steam engines and collapsible paddles to allow her to take advantage of favourable sailing conditions.

In 1825, the Calcutta Steam Committee offered a prize of 20,000 rupees to the first steam vessel that could make the 17,700 kilomtre trip from England to Calcutta and back twice at an average rate of 70 days or less. Captain Johnston journeyed to 67.7 meters long, displaced 479 ton, was equipped with two 60 horsepower steam engines and collapsible paddles to allow her to take advantage of favourable sailing conditions.

The Enterprize left Falmouth on the 16th of August 1826 carrying 17 passengers, dispatches and mail and arrived at Calcutta on the 7th of December after a journey of 113 days. She had used her engine on 62 days and sail on 40 days and had been at coaling stations 11 days. She burning over 10 tons of coal a day to put out 6 knots. Considering that sailing ships were commonly making the trip in 90 day, the Enterprize experiment was a failure. Despite this, Captain Johnson was granted half the prize in recognition of his work in furthering steam navigation between England and India and proving that steamers were capable of long ocean voyages.

Still recovering from the fever he had contracted during the Burmese campaign, Waghorn began preparations for his departed on furlough to England. Before leaving he had communicated his idea for "A steam communication between our Eastern possessions and their mother-country, England" to the Marine Board at Calcutta. The Board favoured his plans and forward them at once to the Bengal Government who issued him with letters of recommendation to the Honourable Court of Directors of the East India Company as a fit and proper person to open steam navigation with India. At every opportunity on his journey home and once arrived in England, he promulgated his plan. Unfortunately, the P&O and all but Mr. Loch, the Chairman of the Board of Directors of the East India Company, were opposed to steam navigation on the open ocean.

Two years latter, Waghorn's efforts payed off when in October 1829, Lord Ellenborough, president of the Court of Directors and Mr. Loch engaged him to carry dispatches to Sir John Malcolm, the Governor of Bengal, by way of Egypt and the Red Sea. The main purpose of the mission was to make a report upon the navigation of the Red Sea, with the view of establishing an overland route for the mails. With just four days notice and taking only 20 pounds of luggage, Waghorn departed from Gracechurch Street on October 28, 1829. He went by way of Trieste and reached Alexandria in 26 days. He crossed the desert to Suez where he was to join the Enterprize. However, she did not show because of having had mechanical troubles. Waghorn would not be stopped, he boarded an open native boat and proceeded down the Red Sea to Jeddah, a distance of 620 miles, which he traversed in six and one half days. He completed the trip by man-of-war and reached India on March 20, 1830 having been en route four months and 21 days. His actual travel time had been 84 days. The trip had taken longer than foreseen because he had fallen ill at Jeddah for a month. In his own estimation, under favourable conditions and steamer connections, the trip could be concluded in 55 days. This journey had convinced him to change his plans from the Cape route to that through Egypt.

While in India he called meeting in Bombay, Madras and Calcutta to advance his ideas to establish steam communication between England and the Far East and was well received. With the thanks of the Governor of Bengal he returned to England. At a meeting with the Mr. Loch's successor, Waghorn was told that the East India Company needed no steam communication with the East at all. Waghorn says that the new Chairman of the Board of Directors to him:

"that the Governor-general and people of India had nothing to do with India House; and if I did not go back and join their pilot service, to which I belonged, I should receive such a communication from that House as would be by no means agreeable to me!"

Waghorn's reaction was, by now, predictable:

"On the instant I penned my resignation, and placing it in his hands, then gave utterance to the sentiment which actuated me from that moment till the moment I realised my aspiration - that I would establish the Overland Route, in spite of the India House."

|

Waghorn's Overland Route

Initially, the British Government and the East India Company were content to leave the overland portion of the route through Egypt to private enterprise because, for the time being at least, neither wanted to risk becoming entangled in political complications with the Pasha of Egypt or the Government of Turkey.

One reason why the East India Company did not support Waghorn's idea was the difficulty of obtaining an adequate supply of affordable coal East of the Mediterranean. It had cost the East India Company £20 a ton to deliver coal to Suez and had taken as much a 15 months to convey it there. Waghorn applied his philosophy of proving-by-doing and set out to demonstrate that it was possible to transport coal to Suez economically. With the help Pasha Mohammed Ali, 1000 tons of coal were delivered to Suez. Waghorn accomplished this by shipping English coal first to Alexandria then by native vessels along the 48 mile Mahmudieh canal connecting Alexandria and the Nile, next the coal was shipped to Cairo and from there it went by caravan to Suez. The total cost at Suez was £4.3s.4d per ton. With this impediment remove, in 1835, Waghorn began his efforts to set up his express business for mails by the overland route. By 1837, he had been appointed the Deputy Agent of the East India Company in Egypt for the supervision of the mails.

The challenge he faced was reducing what had up to that time been an experimental service, to a system that would ran reliably. Steamer service to Cairo was well established. Service in the Red Sea was supplied by steamers of the Bombay Marine until 1840 and by the P&O after that date. It was left to Waghorn to provide the transit across the desert.

Waghorn lived with the Arabs for three years and showed them the benefits of his scheme. He wrote that "Once in the enjoyment of the Pasha's friendship I was enabled to establish mails to India and to keep the service in my hands for four years. On one occasion I succeeded in getting letters from Bombay to England in 46 days..." He set up a regular caravan service and built eight stopping stations, along the 80 miles from Cairo and Suez, for changes of horses teams and for the provision of meals for passengers.

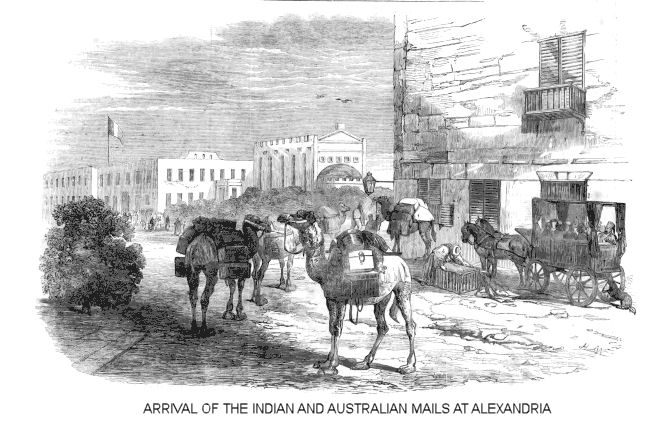

His friendship with the Pasha and his services had made the journey safe and dependable. In time, three hotels were built to service the passenger route. Mohammed Ali opened a house of agency (outpost) in Suez, Waghorn built one at Cairo and another was built at Alexandria for receiving the mails. By the time Waghorn left Egypt, in 1841, he had organised a service using English carriages, vans and horses to transport travellers and had placed small English steamers on the Nile and the canal of Alexandria.

By the Convention of March 30, 1836 between England and France for the transport of the East Indies mail, to spare this mail from having to undergo fumigation and being thus delayed, it was to be sealed in airtight iron boxes. The letters were loaded into 2 by 2 by 1.5 foot boxes which were then sealed with lead. These were bound and stamped with a crown and "General Post-Office, India Mail". A shipment might contain 30 or more such boxes.

Waghorn had agents in the major English cities and in India. The procedure for using his service was as follows: addressed letter were taken to a one of his agents and the sender paid the required fees, the agents applied the handstamp, "Care of Mr. Waghorn etc." and the letter was left with them to be forwarded by the fastest route. John Sidbottom's, "The Overland Mail", published in 1948 remains the outstanding reference on Waghorn's service. Sidbottom illustrates over ten types of handstamps that Waghorn and his agents used to mark letters between 1836 and 1841.

As the steam service to and from Egypt improved and faster routes through Europe were developed, so did the speed of the mails between England and India.

Agents of the Bombay Steam Co., Hill and Raven, set up an express business in competition with Waghorn. They also built hotels at Cairo and Suez and operated a number of rest houses along the desert route for their patrons. Because of financial difficulties, the two competitors were forced to amalgamate in 1841 and became J.R. Hill and Co.

In 1837 the mail system was taken over by the English Government to Waghorn's great loss. In 1843, Arthur Anderson described how the mail cross the desert:

"Indian mails are taken charge of on their debarkation at Alexandria, and until their arrival there from India, by agents of the East India Company. The steam vessels on the Nile and Alexandria are not availed of for the transit of the mails, which are conveyed overland between Alexandria and Cairo on the backs of donkeys, each donkey carrying two boxes of letters. Between Cairo and Suez, across the desert, dromedaries are employed. The average of one monthly mail somewhat exceeds one hundred boxes each way, being upwards of two hundred crossing Egypt to and from India, and containing about one hundred thousand covers."

|

The mail made the crossing in less time (64 hours) than the passengers and their baggage since it did not require rest stops. The steamer at Suez had to wait 24 hours after the arrival of the mail on board before it could leave to allow passengers time to cross the desert and reach Suez.

Once the P&O had established steamer communications on both sides of the Isthmus they sought the control of the overland route because passengers were dissatisfied with the existing service. They felt that Hill & Co. could not handle the increasing traffic and this would compromise their profits. With the help of the Pasha, the P&O formed the Egyptian Transit Company and on the 26th of May 1843, this newly formed Company bought out Hill and Co. The handstamp "EGYPTIAN TRANSIT COMPANY SUEZ" appears on covers dated between 1843 and 1847. Most of these covers show that they went to Alexandria via the British Post Office and from there, by the Austrian Post Office in Alexandria via Trieste, a route which Waghorn had pioneered.

The P&O had made many improvements to their transit system on the Mahmoudieh Canal and the Nile, they introduced improved six passenger carriages on the desert route, the rest-house were upgraded and that at the midpoint was enlarged with clean bedrooms with beds and a dining room with cooks and servants. By 1846 the P&O was carrying mail the 250 miles from Alexandria to Suez in 64 hours, steamer to steamer, and passengers in 12 hours more owing to a rest stop in Cairo. The Egyptian Transit Company was itself taken over by the Pasha's government in 1846.

Leonardo to the Internet: Technology and Culture from the ...

books.google.co.in/books?isbn=1421401541

Thomas J. Misa - 2011 - Science

The initial experiments with steam engines around Calcutta were, from a ... on the Hooghly for a year as a passage boat while the more substantial Enterprise, ... Anearly indication of the value of steamers in imperial India came in the first ...The Steam Engine: Its Origin and Gradual Improvement, from ...

books.google.co.in/books?id=o6wxAQAAMAAJ

Paul Rapsey Hodge - 1840 - Locomotion

In the year 1815, the first passage was made from Glasgow to London, in a ... 1825, a passage was made from London to Calcutta by the steam ship ' Enterprise.The Family Magazine - Volume 3 - Page 500 - Google Books Result

books.google.co.in/books?id=pp_PAAAAMAAJ

1838

In March, 1816, the first steam boat crossed the British channel from Brighton to ... a passage was made by the steam ship Enterprise, from London to Calcutta.

No comments:

Post a Comment